|

Hermes

|

|

Hermes

|

In this section are described the some advanced functions of Hermes MOD.

Object similarity or object dissimilarity or object matching or shape matching is the decision of the resemblance (similarity) between two objects. In general, two objects \(A,B\) are given and the resemblance to each other is extracted. This can be quantitatively expressed as a distance between the two objects [anagnostopoulos2015similarity] :

Measuring the similarity between trajectories is not straightforward mainly because we need to take into account the temporal dimension [vodas2013hermes],[anagnostopoulos2015similarity.] The reasons that makes the calculations more complicated for trajectories are:

To be able to calculate the measure of similarity for the trajectories, one needs to define [anagnostopoulos2015similarity] :

There are many proposed measures in the literature and Hermes implements some of the state of the art methods in its similarity measures library [vodas2013hermes.] The trajectory similarity functions that are implemented in Hermes are shown below.

Many similarity measures on shapes are based on the \( L_p \) distance. For two points \( r = (r_1, ... ,r_d)\) and \( q=(q_1, ... ,q_d)\) in \( \mathbb{R}^d\) the \( L_P \) norm is calculated from equation below:

\begin{equation*} L_{P} (r,q) = \| r - q \|_p = ( \sum_{i=1}^{d}|r_i - q_i|^p )^{\frac{1}{p}} \end{equation*}

The above equation is also often called the Minkoswki distance. \( L_1 \) norm ( \(p=1\)) is named the Manhattan distance or the city block distance and \(L_2\) norm ( \(p=2\)) is the well known Euclidean distance. For \(p\) approaching \(\infty\), we have the maximum norm (Chebyshev norm): \(max(|r_i - q_i|)\). For all \(p \geq 1\) the \(L_P\) norms are metrics and for \(0<p<1\) it is not a metric, since the triangle inequality is not satisfied.

Unless otherwise specified, in what follows, \(A\) and \(B\) will refer to point sets in \(\mathbb{R}^d\), where \(|A| = k\) and \(|B|=n \geq k\) and the underlying metric on points in \( R^d\) is that induced by the \(L_2\) norm.

A simple solution to calculate the similarity is to use an \( L_p \) norm to the sequences of points. Euclidean distance has the advantage of being easy to compute (and specifically it has a linear computation cost and is easy to implement. However, the Euclidean distance outliers have a great impact on the overall distance (due to the fact that is computed by square deviations) and it does not support local time shifting [anagnostopoulos2015similarity.]

Hermes implements 4 functions that use the \( L_2 \) norm:

Below are shown some examples:

WITH

trajectory1 AS(

SELECT traj

FROM imis_traj

WHERE (obj_id, traj_id) = (251, 1)

),

trajectory2 AS(

SELECT traj

FROM imis_traj

WHERE (obj_id, traj_id) = (719, 1)

)

SELECT Euclidean(trajectory1.traj, trajectory2.traj)

FROM trajectory1, trajectory2;

euclideanend

------------------

71013.2007024046

(1 row)

SELECT EuclideanEnd(

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(1,1)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

),

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(2,2)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

)

);

euclideanend

--------------

0

(1 row)

SELECT Euclidean(

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(1,1)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

),

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(2,2)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

)

);

euclidean

-----------------

1.4142135623731

(1 row)

A similar distance to Euclidean distance measure is the Manhattan distance ( \(L_1 \) norm). An example is shown below:

SELECT Manhattan(

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(1,1)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

),

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(2,2)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

)

);

manhattan

-----------

2

(1 row)

A similar distance to Euclidean distance measure is the Chebyshev distance ( \(L_{\infty} \) norm). An example is shown below:

SELECT Chebyshev(

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(1,1)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

),

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(2,2)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

)

);

chebyshev

-----------

1

(1 row)

A generalization of the previously discussed Euclidean distance is the DISSIM function that defines the dissimilarity between two trajectories being valid during the period \([t_1, t_n]\) as the definite integral of the function of time of the Euclidean distance between the two trajectories during the same period [pelekis2014mobility] :

\begin{equation*} DISSIM(A,B) = \int_{t_1}^{t_n} L_2(A(t),B(t)) dt \end{equation*}

In order to simplify the computation of this function, since both trajectories can be represented by the union of their sampled points using linear interpolation, the above definition of dissimilarity is transformed to [pelekis2014mobility] :

\begin{equation*} DISSIM(A,B) = \displaystyle\sum_{k=1}^{n-1} t_i \int_{t_k}^{t_{k+1}} L_2(A(t),B(t)) dt \end{equation*}

where \(t_k\) are the timestamps when moving objects \(A\) and \(B\) recorded their position.

The previous transformation actually decomposes the dissimilarity calculation problem to computing a series of integrals, each of which is upon two 3-dimensional segments, i.e. two points moving with linear functions of time between consecutive timestamps t k and t k+1 . This function still includes complex computations. A solution for this is to approximate the computation of the integrals by using the trapezoid rule. The following equation gives approximated computation of the previous one [pelekis2014mobility] :

\begin{equation*} DISSIM(A,B) \approx \frac{1}{2} \cdot \displaystyle\sum_{k=1}^{n-1} \Bigg(\bigg(L_2(A(t_k),(B(t_k)) + (L_2(A(t_{k+1}),(B(t_{k+1}))\bigg)\cdot(t_{k+1} - t_{k})\Bigg) \end{equation*}

Hermes implements 2 functions that use the DISSIM similarity:

Below are shown some examples:

SELECT DISSIMApproximate(

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(1,1)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

),

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(2,2)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

),

1

);

dissimapproximate

----------------------

(41.0121933088198,0)

(1 row)

SELECT DISSIMExact(

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(1,1)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

),

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(2,2)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

),

1

);

dissimexact

------------------

41.0121932944964

(1 row)

An alternative to Frechet distance which is more appropriate to trajectories is the average Frechet distance, aka dynamic time warping (DTW). The advantage of the DTW is that it allows a sequence to "stretch" or to "shrink" in order to better fit. The definition of DTW uses a recursive manner to search all possible point combinations between two trajectories for the one with minimal distance (see the below figure[pelekis2014mobility] and equation) [anagnostopoulos2015similarity] .

\begin{equation*} DTW(A,B) = L_{P}(r_n,q_m) + min \begin{Bmatrix} DTW(A,Head(B)), \\ DTW(Head(A),B) \\ DTW(Head(A),Head(B)) \end{Bmatrix} \end{equation*}

where \(Head(A) = ((r_{1,x},r_{1,y} ... (r_{n-1,x},r_{n-1,y}))\) (the subsequence \(A\) without the head element).

DTW attempts to match each point with the most appropriate one and finally chooses the shortest distance. If the trajectories contain significant dissimilar portions, possibly due to actual deviations the results are not as meaningful due to the fact that DTW tries to find a correspondence for all points and thus, gives correspondences for points in the deviation for which no meaningful one exists. Another disadvantage of the DTW is that it does not follow triangle inequality making it a non-metric function [anagnostopoulos2015similarity] .

In the current implementation, dtw takes 5 parameters. The first two are the trajectories, the third is a locality constraint. If the locality constraint is negative then someone can use the next parameter to define a percentage of the trajectory to be used in the locality constraint. The final parameter is the \(L_p\) norm to be used. Currently only \(L_1\) and \(L_2\) can be used. An example is shown below:

SELECT DTW(

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(1,1)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

),

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(2,2)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

),

-1,

1,

2

);

dtw

-----------------

1.4142135623731

(1 row)

The Longest Common Subsequence (LCSS) is similar to DTW that it tries to match two trajectories by allowing their "stretching", however, without changing the sequence of elements, while allowing some elements of the sequences to be left unmatched. It can handle possible noise that may appear in data more efficient because it can disregard noisy points [anagnostopoulos2015similarity] .

LCSS can be calculated by the below equation:

\begin{equation*} LCSS(A,B) = \begin{cases} 0 & \quad \text{if } m=0 \text{ or } n=0 \\ LCSS(Head(A),Head(B)) + 1 & \quad \text{if } |r_{n} - q_{m}| < \epsilon \\ & \text{ and } |n-m| \leq \delta \\ max \begin{Bmatrix} LCSS(Head(A),B), \\ LCSS(B,Head(B)) \end{Bmatrix} & \text{ otherwise } \end{cases} \end{equation*}

where \(\epsilon \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(\delta \in \mathbb{Z} \). In LCSS, \(\epsilon\) declares the threshold, which determines whether or not two elements match and \(\delta\) is used to control how far in time we can go in order to match a given point from one trajectory to a point in another trajectory [anagnostopoulos2015similarity] .

LCSS is not a distance but can be converted into one by using the below equation:

\begin{equation*} LCSS_{dist}(A,B) = 1 - \frac{LCSS(A,B)}{min(n,m)} \end{equation*}

Another disadvantage of the LCSS is that it does not follow triangle inequality making it a non-metric function [anagnostopoulos2015similarity] .

In the current implementation, dtw takes 5 parameters. The first two are the trajectories, the third is the \(\delta\) as described above. If the locality constraint is negative then someone can use the next parameter to define a percentage of the trajectory to be used in the locality constraint. The final parameter is the \(\epsilon\) described above. If \(\epsilon \leq 0 \) or \(\epsilon \geq 1 \) then \(\epsilon = min(stedev(trajectories)) \). An example is shown below:

SELECT LCSS(

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(1,1)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

),

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(2,2)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

),

-1,

1,

1

);

lcss

------

0.5

(1 row)

The Edit Distance on Real Sequences (EDR) function is based on the well-known edit distance function which has been succesfully used in applications like bioinformatics where an important task is to quantify the similarity between two strings. Given two strings, the Edit Distance function calculates the minimum number of insertions, deletions and replacements in order for the two strings to become identical. Like LCSS, EDR also uses a threshold \(\epsilon\) to match two points, however the distance may be either 0 or 1, depending on whether they match or not. Applying this matching criterion to two points \(r_i\) and \(q_j\) of trajectories of moving objects [pelekis2014mobility] :

\begin{equation*} match(r_i,q_j) = \begin{cases} 1 & \quad \text{if } |r_{i,x} - q_{j,x}| \leq \epsilon \text{ and } |r_{i,y}-q_{j,y}| \leq \epsilon \\ 0 & \quad \text{else } \end{cases} \end{equation*}

Due to this choise, outliers have much less impact on the overall distance, in comparison to the Euclidean distance or the DTW. On the other hand, a crucial difference with LCSS, is that EDR adds a penalty for the gaps between two matched parts, which is proportional to the gap length. This leads to higher accuracy in calculating the distance, in contrast to LCSS. Given the above, the EDR for two trajectories of moving objects, A and B, with lengths n and m, respectively, is defined as [pelekis2014mobility] :

\begin{equation*} EDR(A,B) = \begin{cases} n & \quad \text{if } m=0 \\ m & \quad \text{if } n=0 \\ max \begin{Bmatrix} EDR(Rest(A),Rest(B) + subcost), \\ EDR(Rest(A),B) +1 , \\ EDR(A,Rest(B)) +1 , \end{Bmatrix}, & \text{ otherwise } \end{cases} \end{equation*}

where \( Rest(A)=((r_{2,x},r_{2,y})...(r_{n,x},r_{n,y}))\) and the subcost is defined as:

\begin{equation*} subcost = \begin{cases} 0 & \quad \text{if } match(r_1,q_1)=1 \\ 1 & \quad \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \end{equation*}

In the current implementation, EDR takes 3 parameters. The first two are the trajectories, the third is \(\epsilon \). \(\epsilon \) declares the threshold, which determines whether or not two elements match. An example is shown below:

SELECT EDR(

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(1,1)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

),

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(2,2)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

),

1

);

edr

-----

0

(1 row)

The Edit Distance with Real Penalty (ERP) tries to combine the advantages of DTW and EDR by using a fixed reference point for calculating the distance of the points that have been unmatched. Moreover, if the distance between the two points is very large, ERP uses the distance between a point and the reference point. ERP is defined by the following equation [pelekis2014mobility] :

\begin{equation*} ERP(A,B) = \begin{cases} \displaystyle\sum_{i=1}^{n} dist(q_i,g) & \quad \text{if } m=0 \\ \displaystyle\sum_{i=1}^{n} dist(r_i,g) & \quad \text{if } n=0 \\ min \begin{Bmatrix} ERP(Rest(A),Rest(B)) + dist(t_1,q_1), \\ ERP(Rest(A),B) + dist(t_1,g) , \\ ERP(A,Rest(B)) + dist(q_1,g) \end{Bmatrix}, & \text{ otherwise } \end{cases} \end{equation*}

In the current implementation, EDR takes 3 parameters. The first two are the trajectories, the third is \(L_p \) norm. Currently only \(L_1\) and \(L_2\) can be used. An example is shown below:

SELECT ERP(

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(1,1)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

),

Trajectory(

ARRAY[

PointST('2008-12-31 19:29:32' :: Timestamp, PointSP(2,2)),

PointST('2008-12-31 19:30:30' :: Timestamp, PointSP(3,3))

]

),

2

);

erp

-----------------

1.4142135623731

(1 row)

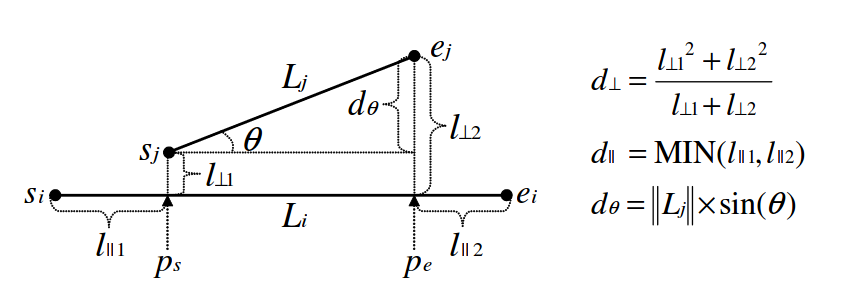

TRACLUS algorithm was introduced by [lee2007trajectory] in an effort to cluster similar trajectories. The main difference from the rest algorithms that cluster trajectories is that it partitions a trajectory into a set of line segments, and then, groups similar line segments together into a cluster and the primary advantage of this algorithm is that is able to discover common sub-trajectories from trajectory database.

TRACLUS framework quantifies the distance between directed segments, which actually correpond to sub-trajectories. More specifically, three component functions are defined between two directed segments, \(L_i\) and \(L_j\): (i) perpendicular \(d_{\bot}\), (ii) parallel \(d_{\parallel}\), and (iii) angular \(d_{\angle}\) distance. The overall distance is simply their weighted sum, where different weights may be used according to different application requirements [pelekis2014mobility] .

An example using the TRACLUS`s distances with Hermes is shown below:

SELECT projectionPointTraclus(

'2247569 4792246'::pointsp,

'2247568 4792243 2246947 4782505'::segmentsp

);

projectionpointtraclus

------------------------

2247568 4792246

(1 row)

SELECT perpendicularDistanceTraclus(

'2247569 4792246 2246943 4782504'::segmentsp,

'2247568 4792243 2246947 4782505'::segmentsp

);

projectionpointtraclus

------------------------

2247568 4792246

(1 row)

SELECT parallelDistanceTraclus(

'2247569 4792246 2246943 4782504'::segmentsp,

'2247568 4792243 2246947 4782505'::segmentsp

);

paralleldistancetraclus

-------------------------

1

(1 row)

SELECT angleDistanceTraclus(

'2247569 4792246 2246943 4782504'::segmentsp,

'2247568 4792243 2246947 4782505'::segmentsp

);

angledistancetraclus

----------------------

4.73320678113542

(1 row)

SELECT traclusDistance(

SegmentSP(PointSP(2337709, 4163887),PointSP(3228259, 4721671)),

SegmentSP(PointSP(2337709, 4163887),PointSP(3228259, 4721671)),

1, 1, 1

);

traclusdistance

------------------

1050433.79154376

(1 row)

According to [wiki:cluster_analysis] clustering is the task of grouping a set of objects in such way that objects in the same group are more similar to each other than to those in other groups.

It takes as input a set of trajectories and a set of parameters and returns a set of clusters and a set of outliers. More specifically, this clustering technique consists of 4 steps. Some global parameters are the Voting Method and Sigma.

The first step is the voting step where each trajectory gets voted by all the other trajectories. The input of the voting procedure is a set of trajectories, and a set of parameters (temporal buffer size, spatial buffer size, sigma). This is achieved by employing the aforementioned TBQ query. The output is a set of voting signals

The second step is the segmentation phase where each trajectory is broken down to homogeneous sub-trajectories w.r.t. their voting. The input of this procedure is output of the voting step, which is a set of trajectories with their corresponding voting signals, and a two parameters w and \(\tau\). The output is a set of sub-trajectories

The third step is the sampling step where from the set of sub-trajectories produced by the previous step the most representatives are selected. The input is a set of sub-trajectories and a set of parameters (temporal buffer size, spatial buffer size, M and eps_ssa). The output is a set of representative sub-trajectories.

Finally, the fourth step is the clustering phase, where the clusters are built "around" the representative sub-trajectories produced by the sampling procedure, which play the role of cluster seeds. The input is the set of the representative sub-trajectories, the set of the rest of the sub-trajectories and a set of parameters (temporal buffer size, spatial buffer size and eps_sca)

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS S2T_Parameters CASCADE;

CREATE TEMPORARY TABLE S2T_Parameters (key text NOT NULL, value text NOT NULL, PRIMARY KEY (key)); --Creating a temporary table in order to store the parameters

INSERT INTO S2T_Parameters(key, value) VALUES ('D', 'imis');--Defining the dataset

INSERT INTO S2T_Parameters(key, value) VALUES ('NN_method', 'Hermes');--Setting the TBQ as the voting approach

INSERT INTO S2T_Parameters(key, value) SELECT 'w', round((avg_trajectory_points + 1) * 0.2)::integer FROM hdatasets_statistics WHERE dataset = HDatasetID('imis');--Setting parameter w which is used for the segmentation phase. Parameter w sets the minimum size of a partitioned trajectory

INSERT INTO S2T_Parameters(key, value) VALUES ('tau', 0.01);--Setting parameter which is used for the segmentation phase. Parameter \form#66 is related with the segmentation sensitivity of our method. As \form#66 increases, the number of sub-trajectories reduces.

INSERT INTO S2T_Parameters(key, value) VALUES ('M', 500);-- Setting the maximum number of representatives to be identified.

INSERT INTO S2T_Parameters(key, value) VALUES ('eps_ssa', 0.001);--Setting the parameter eps_ssa which is used for the sampling phase. It is a positive real number close to zero that acts as a lower bound threshold of similarity between sub-trajectories and representative candidates.

INSERT INTO S2T_Parameters(key, value) VALUES ('eps_sca', 0.001);--Setting the parameter eps_sca which is used for the clustering phase. It is a positive real number close to zero that acts as a lower bound threshold of similarity between sub-trajectories and representatives.

SELECT S2T_Sigma(length(SegmentSP(lx,ly, hx,hy)) * 0.001) FROM hdatasets_statistics WHERE dataset = HDatasetID('imis');--Setting parameter Sigma. This parameter is used in the first, third and fourth step. Sigma shows how fast the function of the "voting influence� decreases with distance.

INSERT INTO S2T_Parameters(key, value) VALUES ('temporal_buffer_size', '0 seconds');--Setting the temporal buffer size of the voting step.

INSERT INTO S2T_Parameters(key, value)

SELECT 'spatial_buffer_size', round(sqrt(-2*(length(SegmentSP(lx,ly, hx,hy)) * 0.001)^2*ln(0.001)))::integer

FROM hdatasets_statistics

WHERE dataset = HDatasetID('imis');--Setting the spatial buffer size of the voting step.

INSERT INTO S2T_Parameters(key, value) VALUES ('temporal_buffer_size_ssa', '0 seconds');--Setting the temporal buffer size of the sampling step.

INSERT INTO S2T_Parameters(key, value)

SELECT 'spatial_buffer_size_ssa', round(sqrt(-2*(length(SegmentSP(lx,ly, hx,hy)) * 0.001)^2*ln(0.001)))::integer

FROM hdatasets_statistics

WHERE dataset = HDatasetID('imis');--Setting the spatial buffer size of the sampling step.

INSERT INTO S2T_Parameters(key, value) VALUES ('temporal_buffer_size_sca', '0 seconds');--Setting the temporal buffer size of the clustering step.

INSERT INTO S2T_Parameters(key, value)

SELECT 'spatial_buffer_size_sca', round(sqrt(-2*(length(SegmentSP(lx,ly, hx,hy)) * 0.001)^2*ln(0.001)))::integer

FROM hdatasets_statistics

WHERE dataset = HDatasetID('imis');--Setting the spatial buffer size of the clustering step.

SELECT S2T_VotingMethod('Trapezoidal');--Setting the Trapezoidal as the distance function.

SELECT S2T_Clustering();--The function that performs the clustering

Hermes provides a set of functions that allow to construct a KML document within a query in steps. In particular:

By enclosing a folder element into a KML document element, a KML file is ready to be written into a system file using �COPY� command. But before someone could export the results of a query he should create a directory where PostgreSQL has access. An example of how we visualized the Timeslice query is following:

COPY (

WITH

TABULAR_RESULT AS (

SELECT DISTINCT ON (obj_id,traj_id) obj_id,traj_id,

atInstant(seg, '2009-01-02 00:00:00') AS position

FROM imis_seg

WHERE seg ~ '2009-01-02 00:00:00' :: timestamp

)

SELECT KMLDocument(KMLFolder('2009-01-02 00:00:00',

string_agg(KMLPoint('MMSI : ' || obj_id,getSp(position),

HDatasetID ('imis')), ' ')))

FROM TABULAR_RESULT

) TO '/home/anagno/Timeslice.kml';

The produced file is shown in Timeslice.kml.

Another more complicated example is shown below:

COPY (

WITH

TABULAR_RESULT AS (

WITH

TO_METERS AS (

SELECT

PointSP(PointLL(23.59, 37.91), HDatasetID('imis')) AS low,

PointSP(PointLL(23.65, 37.96), HDatasetID('imis')) AS high

),

SPT_WINDOW AS (

SELECT

BoxST(Period('2008-12-31 23:00:00', '2009-01-01 01:00:00'),

BoxSP((SELECT low FROM TO_METERS), (SELECT high FROM TO_METERS))

) AS box

)

SELECT obj_id, traj_id, (atBox(seg, (SELECT box FROM SPT_WINDOW))).s

AS seg

FROM imis_seg

WHERE seg && (SELECT box FROM SPT_WINDOW)

AND (atBox(seg, (SELECT box FROM SPT_WINDOW))).n = 2

)

SELECT KMLDocument(KMLFolder('Input area',

KMLPolygon('Piraeus port area',

BoxSP(PointSP(PointLL(23.59, 37.91), HDatasetID('imis')),

PointSP(PointLL(23.65, 37.96), HDatasetID('imis'))),

HDatasetID('imis'))) || string_agg(tracksFolder, ''))

FROM (

SELECT obj_id, KMLFolder('MMSI: ' || obj_id,

string_agg(trackPlacemark, '')) AS tracksFolder

FROM (

SELECT obj_id, traj_id, KMLTrack(

'MMSI: ' || obj_id || '<br/><br/>' ||

count(*) - 1 || ' points sampled between ' || min(getTi(seg)) ||

' and ' || max(getTe(seg)) || '.<br/><br/>' ||

'The ship covered a distance of ' ||

trunc(metres2nm(sum(length(getSp(seg))))::numeric, 1) ||

' NM with an average speed of ' ||

trunc(mps2knots(sum(length(getSp(seg))) /

extract(epoch from max(getTe(seg)) - min(getTi(seg))))::numeric

, 1) || ' knots.'

, array_agg(seg ORDER BY getTi(seg) ASC), HDatasetID('imis')

) AS trackPlacemark

FROM TABULAR_RESULT

GROUP BY obj_id, traj_id

) AS tracks

GROUP BY obj_id

) AS folders

) TO '/home/anagno/postgresql/Range.kml';

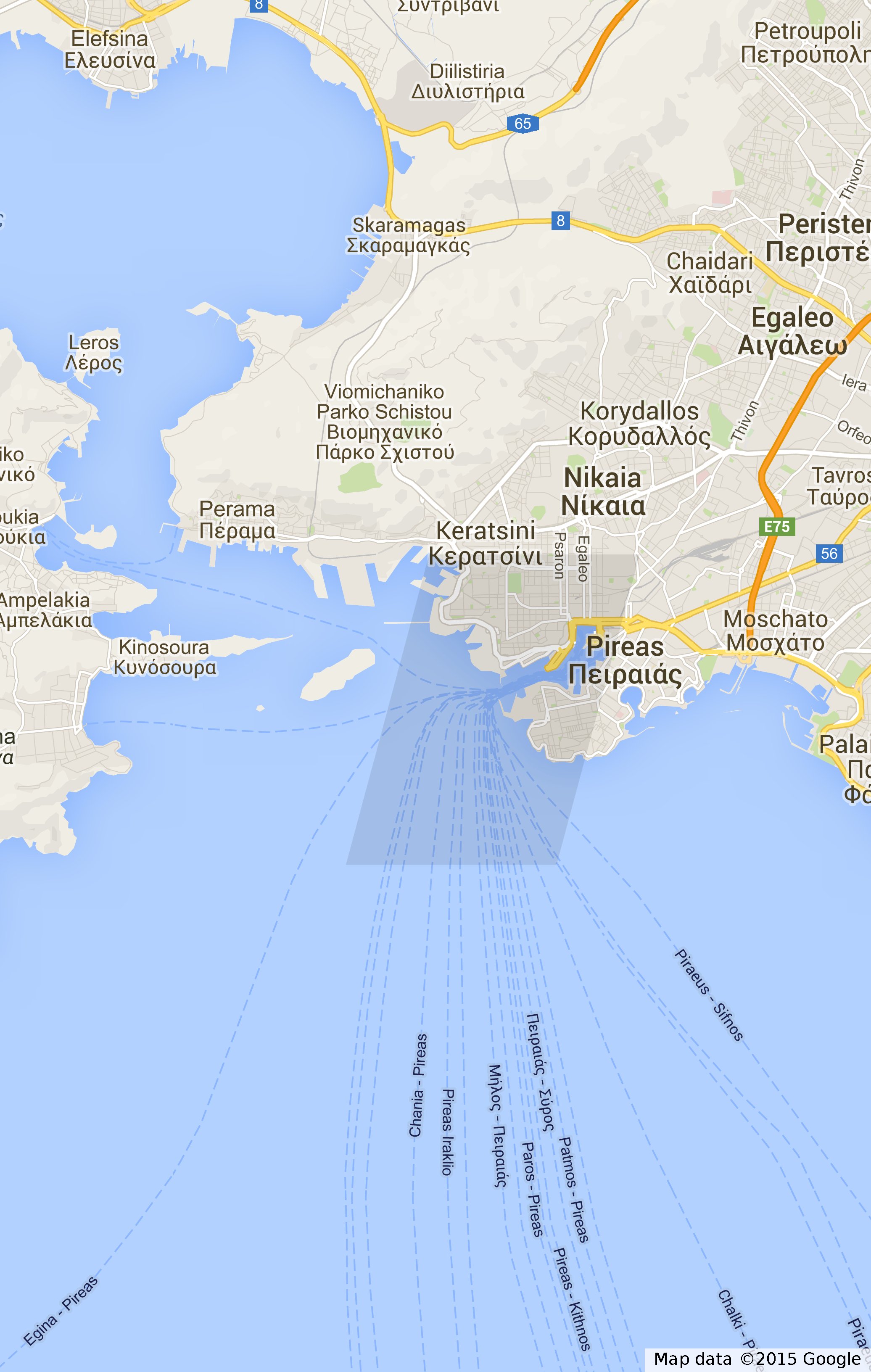

In this example we answer the query "Find the movement of ships inside the area of Piraeus port at New Year`s eve 2009 (range query)" that was presented in the Functions & Operators and afterwards using the visualization functions we export the result to a file.

Again the produced file is shown in Range.kml .